August 28, 2016

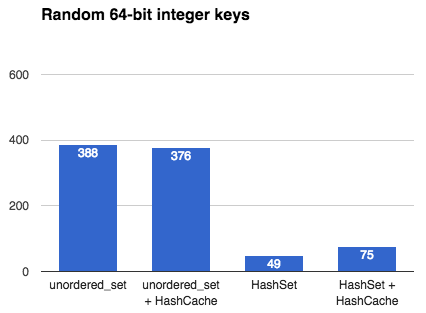

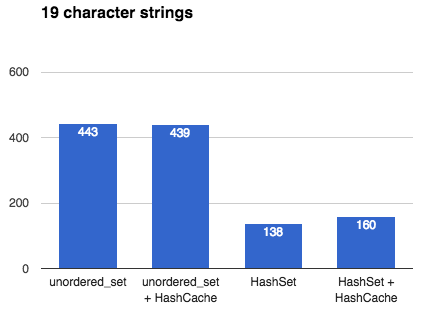

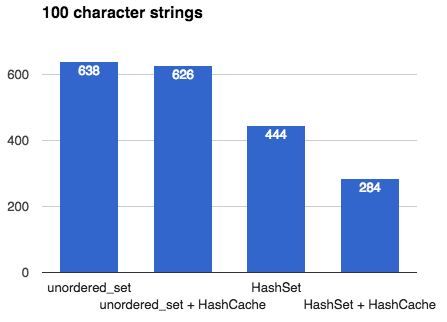

## Intro This article describes the many design decisions that go into creating a fast, general-purpose hash table. It culminates with a benchmark between my own [`emilib::HashSet`](https://github.com/emilk/emilib/blob/master/emilib/hash_set.hpp) and C++11's [`std::unordered_set`](https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/unordered_set). If you are interested in hash tables and designing one yourself (no matter which language you are programming in), this article might be for you. ## Hash tables [Hash tables](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_table) are a wonderful inventions. They allow you to insert, erase and look up things in [*amortized*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amortized_analysis) *O(1)* operations ([*O(√N)* time](2014_04_21_myth_of_ram_1.html)). By *amortized* we mean that on average an operation (e.g. an insertion) takes is an *O(1)* operation, but occasionally it may take more time. In particular, when a hash table is full, an insertion will trigger a *rehash*. In a rehash, a new table will be allocated and all keys will be moved into this new (larger) table. ## Hash tables in C++ Since C++11, STL ships with two hash tables: [`std::unordered_map`](en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/unordered_map) and [`std::unordered_set`](en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/unordered_set). They where designed to have an interface very close to the old (ordered) [`std::map`](en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/map) and [`std::set`](en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/set). The advantage of this is that it's easy to port old `std::map`/`std::set` code to the new unordered variants and get a nice speed boost. The disadvantage, however, is that STL:s hash tables are much slower than they have to be. The reason is that the standard mandate that any insertion or deletion of an element must not affect *pointers to other elements*. This means a rehash may not move elements in memory. The memory for an element must thus be allocated once, and never moved. This means that C++11's hash tables must have an array that *points* to its elements rather than contain them directly. This means that any lookup in the hash table incurs one extra pointer chasing, and thus a likely cache miss. As we shall see, this may make a hash table an order of magnitude slower than it has to be. ## Making your own hash table Like many others I've made my own hash table. I've written it in my preferred language of C++, but the design decision carries over to other languages too. **Design goals:** 1. Make it fast. 2. Don't make decisions for the user unnecessarily. 3. Assume the user is using a good hash function. (In fact, design goal 3 can be derived from the previous two: if you have a bunch of random integers (random in all bits) you don't need to hash them at all. But if you have something like pointer addresses you very much need to hash them (to spread the entropy to all bits). The hash table cannot know which types of input you are giving it, so by design goal 2 we push that decision to the user.) Here's some of the major design decisions: ## [Chaining]("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_table%23Separate_chaining") or [Open addressing]("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_table%23Open_addressing")? Chaining is what your STL implementation is most likely using, as it makes sense when you're allocating each bucked separately anyway. The advantage is that once an element is the table, you can safely point to it without risking it will move. The disadvantage is that it is much slower than open addressing (as explained above). **Decision: Open addressing**. It is faster, and thus satisfies design goal 1. But what if the value we're storing is slow to move, or immovable? Or what if we want the feature of being able to point to it once and never worry about it moving during a rehash? Simple! Just add the layer of indirection yourself: just use a `HashMap<Key, std::unique_ptr<Value>>`! This satisfies design goal 2. ## Power-of-two or prime numbers? When the user wants to look up an element in the hash table we first need to hash the key, and then map that hash value to the size of the table. This is called *constraining* the hash value. This is done by taking the hash value modulo the table size. But what should the table size be? There are two main philosophies: either we constrain the size of the table to be a power-of-two, or to be a prime number. The advantage of a prime number is that you will use all bits of the hash value. The advantage of using power-of-two is that we don't need to look for prime numbers, and we don't need to do an expensive modulo operation (we just need a dirt-cheap bit mask). **Decision: Power-of-two**. It is faster, and thus satisfies design goal 1. But what about using all the bits of the hash value? Well, by design goal 3 we don't *need* to use all bits – because a good hash function will spread the entropy well anyway. ## [Linear probing]("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linear_probing") or [quadratic probing]("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quadratic_probing")? What if we insert a key and the bucket it should fall into is already occupied? Then we need to put it in another bucket. One way to do that is to put it in the next empty bucket. The problems with that is with a bad hash functions you can get really bad collision chains where you need to go through many elements to find an empty bucket. One solution to this is to use quadratic probing, where you first skip one element, then two, then four, etc. **Decision: Linear probing**. By design goal 3) we don't need to handle bad hash functions and linear probing is much faster than quadratic probing (due to cache locality) and thus we satisfy design goal 1. ## Recompute hashes on each rehash, or [memoize](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization) them? When rehashing we need to re-calculate the (unconstrained) hash value for every key. If the hash function is slow we might win some performance by storing the hash value with every key, at the cost of some space. Another advantage of this can be quicker equality tests during collisions: we can first compare the unconstrained hash values before comparing the actual keys (which may be long strings and thus slow to compare). **Decision: Don't memoize hash values**. This stems from design goal 2: don't make decisions for the user. If the hash functions is fast, storing its result will waste space and time thus violating design goal 1. Instead, the user can chose to cache the hash value inside the key type. This is the idea behind [`emilib::HashCache`](https://github.com/emilk/emilib/blob/master/emilib/hash_cache.hpp): a small wrapper type that is there just to memoize the hash function. !!! note **Side-note**: I remember writing a hash table for Java back in university (2003 or 2004), and memoizing the hash value had a huge positive impact on the execution time. That's because comparing two things for equality in Java mean a virtual function call (`Object.equals`) and thus is slow as hell. In the ends, optimizing Java is like trimming a [Trabant](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trabant) for a Formula One race.) ## Benchmark So, this the all the above translate to actually wins? To test it, I [wrote a benchmark](https://github.com/emilk/emilib/blob/master/benchmarks/hash_cache_benchmark.cpp) where I insert a million unique keys into either an `std::unordered_set` or an `emilib::HashSet`, with and without using `emilib::HashCache`. They keys are: * One million random 64 bit numbers (e.g. `2947667278772165694`). * The above numbers, but encoded decimally as `std::string`s (e.g. `"2947667278772165694"`). This is to emulate realistic real-world data with high entropy. * The above string with a hundred extra `x`:s appended (e.g. `"2947667278772165694xxxxxxxx…"`). This is to make the cost of hashing the string a bit more costly. I run each benchmark ten times and take the best time. The compiler is Clang and the platform is OSX. ## The results: All numbers are in milliseconds and **lower is better**.  Using `emilib::HashCache` is obviously a waste of space and time, but the raw wins of `emilib::HashSet` over `std::unordered_set` are impressive. These are the speedups you can expect when the key is small (e.g. an integer or a pointer). ------------------------------------------  Here `emilib::HashSet` is still superior to `std::unordered_set`, but not by as much. More time is spent allocating and hashing individual keys. Again, memoizing hash values is a waste of time. ------------------------------------------  Finally `emilib::HashCache` shows its use: by saving us from recalculating the hash of a hundred bytes on each rehash we make significant savings, but only when using `emilib::HashSet` ## Conclusion Writing your own hash table is a fun exercise, and by using something better than `std::unordered_map`/`std::unordered_set` you can get significant saving. Caching hash values can be worth it if your keys are long. Feel free to make use of my [`HashMap`](https://github.com/emilk/emilib/blob/master/emilib/hash_map.hpp), [`HashSet`](https://github.com/emilk/emilib/blob/master/emilib/hash_set.hpp) and [`HashCache`](https://github.com/emilk/emilib/blob/master/emilib/hash_cache.hpp) – they are single-header and in the public domain. !!! note [Discussion on reddit](https://www.reddit.com/r/programming/comments/500x90/designing_a_fast_hash_table/).